Applying the Theory of Constraints to a Distribution Center

Part 1

Herbie is in your distribution center. He could be at the receiving dock. He could be in picking. He could be in put-away. Or he could be on your shipping dock.

Herbie is in your distribution center. He could be at the receiving dock. He could be in picking. He could be in put-away. Or he could be on your shipping dock.

Let’s push that fat kid out the dock door.

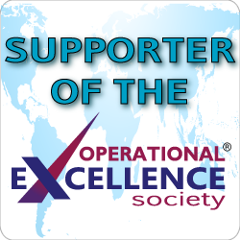

Eli Goldratt’s book "The Goal" introduced the concept of a "Herbie" to industrial engineers and plant managers. The book is the first business novel. In one part, the plant manager hikes with his kid's Scout troop, which has trouble keeping together or making progress. The troop has a constraint - the speed that Herbie, the fat kid, can walk. Figuring out how to get Herbie moving faster and where to put him helps the plant manager understand the constraints in his plant.

What is a constraint? It could be a bottleneck in a manufacturing process. It could be the number of doors on your dock. It could be staff, an aisle, a system; almost anything can be a bottleneck.

In "The Goal," the plant manager/protagonist takes his son’s Boy Scout troop out for a hike in the woods. While the troop starts out in an evenly spaced column on the trail, soon the spacing between the boys stretches out until the lead boy is far ahead of the tail of the line. Along the way, our plant manager is thinking about dependent processes and the statistical variance of task completion times. The bottleneck ends up being the fat kid in the troop, Herbie. In the story, our plant manager learns a key to managing bottleneck, moving Herbie’s position in the line, eventually placing him in lead.

If you have not read "The Goal," you should. It will change the way you think about the mission of your distribution center and give you ideas about how you can increase throughput.

In 2005, I had a chance to apply what I learned from my reading of "The Goal." The receiving operations proved to be a serious bottleneck in a distribution center I optimized. Adding additional staff or working overtime failed to clear up the backlog. The DC would work an extra day to clear out the backlog, only to be behind in volume early the following week.

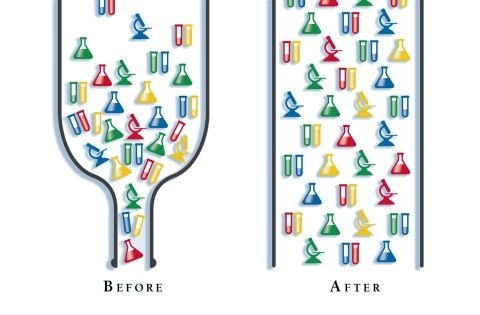

We had started to collect inbound carrier data in 2004; data that included the carrier, the shipments on the deliveries, and the number of pallets. Looking deep into this data, we discovered that in any given week, an average of 42 different carriers delivered to this DC. Filtering out the TL deliveries, we discovered 29 LTL carriers delivered to this DC—over half of them. Two of the LTL carriers used a drop-trailer program, the rest live-unloaded.

Our first suspicion focused on carrier arrival performance. The DC’s receiving manager complained that many of the carriers failed to set appointments, or would show up late for their appointments. When we dug into the data, we found that while some problem children did exist, late arrival for appointment or failure to make an appointment was not the problem.

These carriers delivered to this DC almost every day, an average of 3.9 times a week, and averaged 1.6 pallets per delivery. On a typical day, 26 trucks delivered a total of 40 pallets. Each of these truck-to-dock events took about 30 minutes, the typical appointment, for a total of about 14 hours of dock time. Our crews could typically turn a full truckload in about 45 minutes, pulling an average of 24 pallets quickly. The receiving teams could not turn the LTL loads faster because of the time needed to spot the truck and complete the paperwork.

These carriers delivered to this DC almost every day, an average of 3.9 times a week, and averaged 1.6 pallets per delivery. On a typical day, 26 trucks delivered a total of 40 pallets. Each of these truck-to-dock events took about 30 minutes, the typical appointment, for a total of about 14 hours of dock time. Our crews could typically turn a full truckload in about 45 minutes, pulling an average of 24 pallets quickly. The receiving teams could not turn the LTL loads faster because of the time needed to spot the truck and complete the paperwork.

The bottleneck had not existed a year before. Our inbound data did not go back past mid-2004, but we could tell from our payroll and incentive program data that the problem was something new. We followed up with our inventory management team and learned that they had made changes in the order size and frequency of many vendors, moving to smaller, more frequent shipments to lower the overall inventory in the network. Many of the vendors were new to our company, and used carriers that gave them low rates. A great goal, this helped improve operating cash flow by liberating working capital tied up in inventory, but also led to higher costs in the DC and more performance variability.

Herbie was on our dock. He rode in with every vendor-paid LTL order.

Hello! My name is Dave Schneider, I'm founder of WATP. You may not know Herbie, but believe me, he knows you. And he's not here to help. I'd love to help you find him hiding somewhere in your DC.

Hello! My name is Dave Schneider, I'm founder of WATP. You may not know Herbie, but believe me, he knows you. And he's not here to help. I'd love to help you find him hiding somewhere in your DC.

Give me a call anytime at 877-674-7495