Modeling Long Lead Times

Part Two

Just before we placed the order with the vendor came the email from the CFO.

“Do not order.”

That did not make sense to us. We were overstocked, but not that overstocked. Cutting one order trimmed 175 units of inventory flow that wasn't due to arrive for five weeks. Who knew what would happen? We thought that just cutting one week was kind of drastic, but two weeks of orders, in a row?

That did not make sense to us. We were overstocked, but not that overstocked. Cutting one order trimmed 175 units of inventory flow that wasn't due to arrive for five weeks. Who knew what would happen? We thought that just cutting one week was kind of drastic, but two weeks of orders, in a row?

We talked to the buyer. He was busy working on the next promotion, and did not appear to be worried. We told him we thought that in six weeks we would run out of stock. In fact, we were sure of it.

We were wrong. It was five weeks.

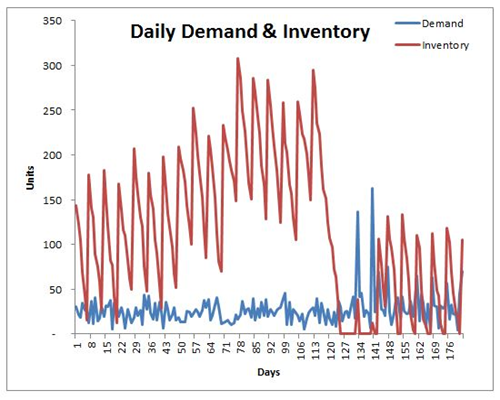

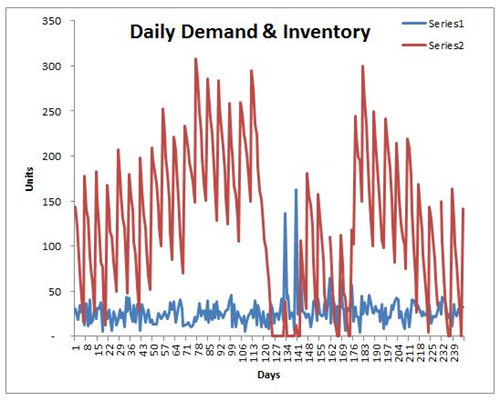

After the inventory spiked up to 308 units on day 77, demand started to pick back up. Nobody knew why; there wasn’t any advertising. We did not start to figure it out until after we looked at the sales around day 100, 14 weeks into the new program, and after we'd held off ordering product for two weeks. From week 11 through week 14, the average daily demand was 28 units, three over par. That rise in inventory carved inventory, not a lot, but we could see the trend as the highs and lows dropped each week.

By the beginning of week 15, we started to get a little worried. The average daily demand picked up on all of the SKUs in the line, not just this one. Since week 13, the second week that the CFO told us to skip ordering, our average daily sales were 27 — two above par. With 260 units in stock, and another 175 due in before we got to the first skipped order, we had 435 units to sell. If demand remained at 27 units, we had 16 days of sales on hand. We would run out of stock in 16 days, after which we might be out of stock for as long as 12 days!

We had no options. With a five-week lead time, ordering more was not the answer.

We called the buyer and told him the bad news. He freaked out. Then he got mad … at us, for running out of stock. After that, he asked how long we would be out of stock. When we said it could be as bad as 12 days, he freaked out again. Then he hung up.

My boss said to track the unfulfilled demand on the item. That was easy; their system did that for us by tracking the number of units the stores ordered that the DC did not ship. About an hour later the buyer called and told us the vendor could not get us any product sooner — they sold the orders that we would have bought to other retailers. He asked about the other SKUs that we ordered from this supplier. Thankfully, we had plenty of stock of those. That is when he said that without this SKU, the sales of those SKUs would drop, because they were like accessories for this product.

We calculated that the lost margin could be as bad as $7,500 on just this one SKU, and perhaps another $4,000 for the other SKUs that would not sell because we were out of stock on this SKU.

My boss looked at the number. He knew that we had other out-of-stocks, but this one SKU proved to be the leader for the sales of about 20 other SKUs. Now it was critical. Because it was no longer a new item, he said that we needed to add some safety stock. First, we had to stop the bleeding.

He asked, “What happens when we are out of stock for 12 days?”

Across the stores, the average demand was 25 units. The stores all carried some stock, but not enough; not 12 days of stock. All got at least one order per week, and some got two orders. They would all be out of stock or close to it within two weeks. If they went out of stock, all the stores would order up to their stock max. With 15 stores in the chain, we figured the average store would order to the max — 6 units. Some smart store managers might order up more, so we estimated that half of the stores would order 12 units apiece, and the rest would order six in their first order after getting back in stock.

132 units of demand, just to get back into stock, and then the demand would settle down to the average. Total demand for the week would be at least 200 units. The one shipment would not be enough.

“Order another load today,” my boss said with an even tone. “We are going to run out again, but if you order today, perhaps the second wave of stock-outs will be small.” We placed another order in the middle of week 15, and again at the beginning of week 16. The vendor questioned the extra order, but said they could fill it.

We got lucky. We did not run out of stock as quickly as we thought we would. Near the end of week 17, we ran out. The next shipment would arrive eight days later. It took a few days before the stores called the DC, and then called the buyer. The DC told them they knew they would get more in the following week. The buyer did not return the calls. The DC called us, and we told them to be ready for big orders on this SKU, and others too.

We knew it would be big, but not that big. The day after the DC received the next load, they called to say they were out of stock again. The store managers issued rain checks for the product, and kept track of the customers to whom they issued those rain checks. All the store managers manually overrode the system, ordering what they needed to cover all of the rain checks. The first day in stock the DC shipped 136 units, five times the average.

The DC was out of stock six days. My manager knew that we would see a second wave. What he did not expect was the reaction of the store managers. While they were out of stock, more people wanted to buy the product. And the managers issued more rain checks. And they again manually increased their orders, this time totaling 163 units in the first day after the load came in.

Thankfully, the extra truck we ordered in the rotation arrived.

Recovery

It was week 20 when we realized that we still did not have enough inventory in the pipeline to recover. We placed another mid-week order as a make-up, and on week 25 that order rolled in. The DC inventory shot up again, almost as high as it was before the CFO got involved. We held our breath, hoping the inventory would work down, and that we would not get another “Do Not Order” email.

We didn’t. But it wasn’t long before we ran out of stock again and had to slip another extra order into the mix, and rework the inventory.

This time, we did not rely on 25 units as safety stock. We pushed the safety stock to 50 units, and after a while the demand started to settle. We never expected the store managers to issue so many rain checks, or for so many customers to redeem them.

Could we have avoided the OSWO’s (Oh Shoot, We’re Out) with the right safety stock? Perhaps. We needed to understand that this one SKU drove the sales for another 20 SKUs. They depended on this SKU to be in stock. Perhaps we could have carried more stock on this one SKU, and less of the others, and still kept in the $300,000 working capital limit.

No amount of safety stock would have kept the CFO from issuing the “Do Not Order” directive. It would be easy to blame him (and we did), but we did not know why he had issued the directive.

In the end, safety stock does not prevent stock outs; it only reduces the risk of running out of stock. Demand and supply vary, sometimes much more then we expect.